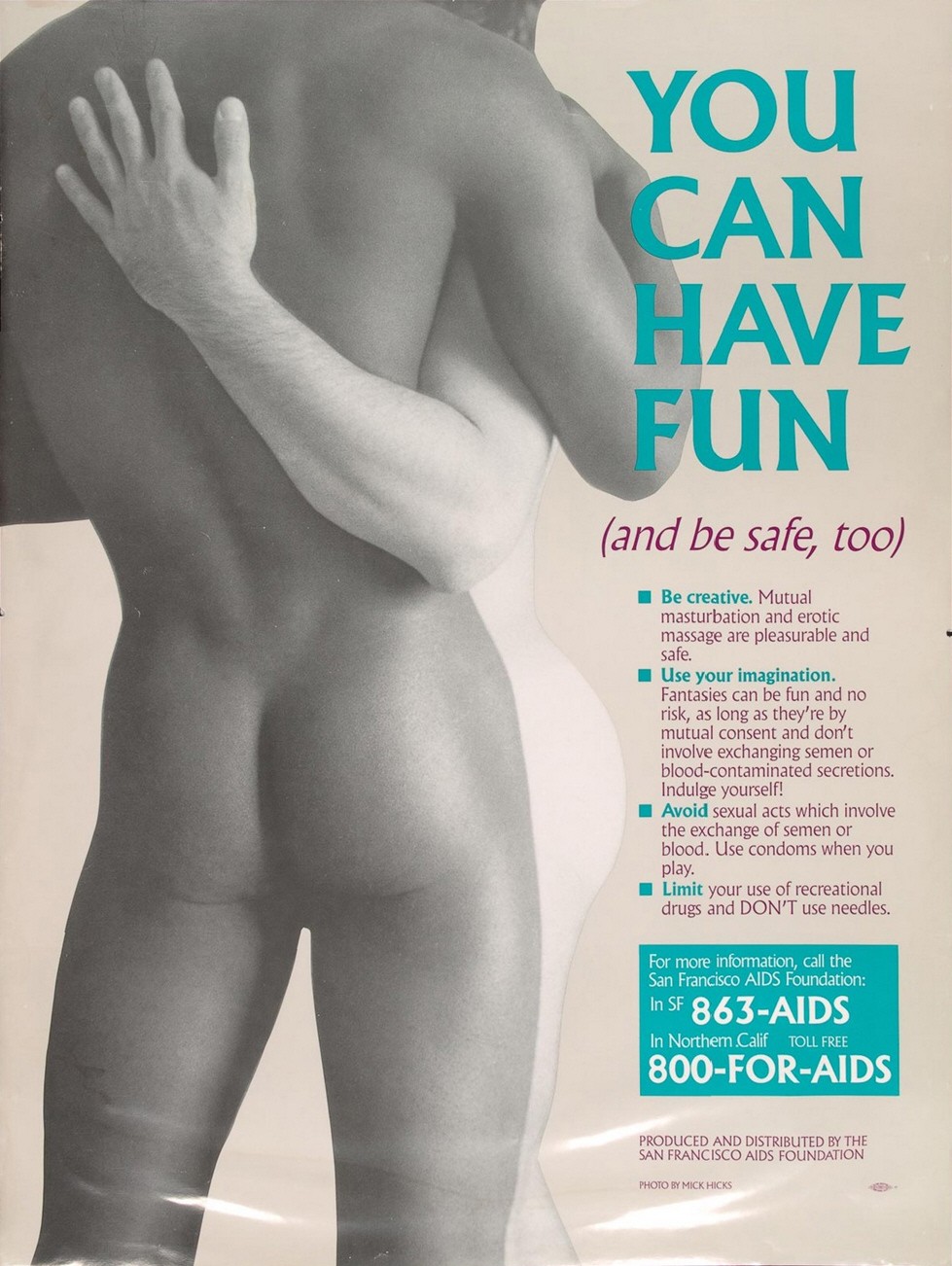

The Poster That ‘Normalized’ Gay Sex

By Daniel Demers, The Gay & Lesbian Review WORLDWIDE contributing writer.

“FRIENDS and acquaintances were going to the hospital in droves,” recalled Robert Gray in a recent interview, reflecting upon the situation for gay men in 1984. “I remember men walking around the Castro with canes—that’s how you knew they were sick—the lesions on the bottoms of their feet were painful, and so they used canes to minimize the pressure when they walked. It seemed like hundreds and hundreds of canes.” Like everyone else at the time, he was scared and worried, “Is it going to hit me?”

Gray, a native San Franciscan and an out gay man, wished there was something he could do, when out of nowhere he was approached by a man who asked if he’d be willing to pose for a safe-sex poster for the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. Gray’s near-perfect physique—enhanced by long hours at the gym—made him the perfect candidate for what the Foundation wanted to communicate. He was asked to meet with photographer Mick Hicks. Hicks, who had studied photojournalism at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, worked for literally all the gay newspapers in San Francisco during the 1970s and ’80s, covering gay life, celebrities, events and parties.

By 1984, Hicks had been working for a year and a half on a series of photos of people with AIDS, chronicling their struggle with the disease “up until they died.” He was also working with a nurse on developing an instructional slide show to be used to teach healthcare workers about AIDS. “Doctors and nurses were unsure and scared,” he recalled. “They would wear rubber gloves and masks when they saw gay patients.” The medical profession hadn’t quite figured out exactly what was causing AIDS—although it was pretty clear it was being transmitted sexually and intravenously through dirty needles. Hicks was asked by Rick Crane, director of the Foundation, to shoot a photo for a safe-sex poster.

On a cold San Francisco morning, Gray arrived at the Noe Valley flat where Mick lived with his partner, Nick Cuccia. Cuccia, then 32 and an editor at The Oakland Tribune, was conveniently enlisted to be the second model in the shoot that took place in the living room. Cuccia didn’t know Gray, and he remembers it as an almost surreal experience: “a couple of naked guys embracing on a cold morning while Mick took fifty or so photos.” It was the first time either had posed naked with another man. Cuccia also recalls the controversy the poster stirred when it found its way into a column in The San Francisco Chronicle by columnist Herb Caen, who wrote: “the black guy was athletic and buff, but for some reason the white guy is an overweight blob with an enlarged posterior.” Cuccia laughingly told me recently, “I didn’t have a model’s body, but I wasn’t overweight either and I didn’t have a big butt!”

For Gray, who was 24 and working in construction, the controversy also hit home personally—but in a different way: he was still living with his parents. He remembers watching the local news with his mom and dad when the poster flashed on the screen as a reporter discussed it and the interracial controversy. He hadn’t come out yet. He told me: “My heart pounded with worry that mom and dad were seeing me naked embracing a white guy and realized I was gay.” He was relieved when they didn’t make the connection.

Crane told me that the poster was created as a “baby step” with a couple of messages. At the time, “everybody was afraid of sex, and we wanted to promote the idea that gay sex was positive if men would simply use condoms,” he said. Using an interracial couple subtly highlighted a deeper issue: “Gays as a group were considered second-class citizens and, ironically, gays themselves were treating gay blacks the same way—as second-class citizens.”

The poster caused an immediate sensation. Crane noted that many gay bars in the city found the racial overtones of the poster unacceptable and refused to display it. Nevertheless, it went on to be displayed in bathhouses and bars from San Francisco to New York, and even found its way to Australia. It was the first of several iconic posters to portray gay sex as normal—and that was a jarring idea at a time when homosexuality was widely viewed as deviant, while AIDS was proof of God’s wrath. The poster’s narrative message, which advocated “mutual masturbation and erotic massage” as alternatives to anal sex, was shocking for its frank specification of sex acts that were still considered taboo.

Today, at 54, Robert Gray is still an imposing figure. He owns and operates Cuts on the Green, a barbershop in the upscale Northwood Golf and Country Club in Sonoma County’s Monte Rio community. He and his husband Charles “Chuck” Prince have been together for 34 years.

Cuccia and Hicks each left San Francisco in 1986 for separate adventures. Cuccia, now 62, moved to L.A., where he spent 21 years as an editor and designer at The Los Angeles Times and now works as a software trainer and consultant. He is a long-term survivor of HIV, having been diagnosed in 1985. Hicks, 67, continued his passion for photography in Boston and San Diego before settling in L.A., where today he specializes in portraiture and feature-film promotional stills.

Reflecting on the times and upon the devastating toll taken by AIDS, Rick Crane commented that it’s remarkable “that all the principals [Cuccia, Gray, Hicks and himself] survived the AIDS crisis, and all are still alive and able to describe the poster’s genesis.”

Copyright 2011 DanielDemers.com - All Rights Reserved

C.B. Web Designs

Courtesy of:

CLICK ON POSTER ABOVE TO VIEW FULL SIZE.

E-MAIL ME ddemers901@sonic.net