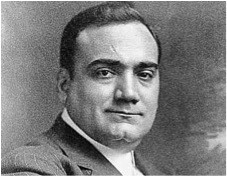

In September of 1919, Enrico Caruso, along with his new bride, arrived in New York harbor aboard the passenger liner Giuseppe Verdi. Suffering from a cold, reporters noted he was “blowing his nose three times a minute” as the ship was moored to its dock in Jersey City. The 46-year-old operatic tenor had married 26-year-old Dorothy Benjamin the previous year. Caruso was returning on the passenger liner which had begun in Genoa, Italy with stops in Naples and the Azores. The ocean voyage had taken twenty-one days. He and his young bride had just spent time at his sixteenth century “Villa di Bellosguardo” described as a “palatial country house near Florence.” He purchased the villa in 1906.

The Naples-born tenor started his musical career as a street singer in Naples and also performed at cafes and private parties. At 22, he made his professional operatic debut in Naples. He joined the New York Metropolitan Opera in 1903, quickly becoming its superstar. As the first person to sell a million recordings, he became immensely wealthy and gained worldwide fame. In 1920 he was paid $10,000 a night to sing in Havana, Cuba [$120,000 in current values].

At the end of World War I, Italy, like many European nations witnessed civil unrest and government collapse. The country was in such debt that it couldn’t even pay its national legislators—leading to wide scale bribery and corruption. For a while local Soviets—communist enclaves—took over government functions. This was the case in Florence and the area surrounding Caruso’s villa. The unrest led to the rise of Dictator Benito Mussolini and his Fascist Party.

THE WRITINGS OF

DANIEL J. DEMERS

Saving Caruso’s Chickens

By Daniel Demers, Palate Press contributing writer

E-MAIL ME ddemers901@sonic.net

When Caruso and his wife arrived at the villa “a hundred and fifty of the neighbors came to the gates and cheered—a touching welcome home,” he told reporters. He went down and talked to them and they told him “with tears in their eyes that they had been without wine and cheese all through the war.” The compassionate tenor “opened the gates” and invited them in and had “wine and cheese brought out to them and they feasted,” he reported.

An hour or so after the initial crowd had gone home another crowd of three hundred arrived with official looking papers imprinted with “wax seals and ribbons.” The documents asserted the crowd’s leaders represented the ‘Public Commissary’ “with authority to confiscate all ‘surplus’ food and wine.”

Caruso objected to the confiscation and offered to sing for them. “I sang as well as I could… [and]…they applauded,” he told the assembled newspapermen. Then they broke down the gates to the villa and “swarmed through my house [carrying away] two tons of wine…a hogshead [63 gallons] of the best olive oil…four dozen of my finest hams…and I know not how much cheese,” he continued.

Dorothy Caruso was able to avert “one tragedy.” Caruso proudly related how the crowd was “about to take away all my chickens and wring their necks and cook them and eat them.” The chickens were his wife’s pets. “Many of them she had named…she could not have their necks wrung.” Dorothy pleaded with the proletariat and, according to Caruso, “they relented. The chickens were saved.” When Caruso died two years later, his chickens at “Villa Bellosguardo,” were reported to still be alive.