How 2 Men Changed Dentistry Forever

school children. The same year Dr. Fones issued a report covering the five-year history of the program that contained some rather amazing statistics. He claimed his program had cut by 50% the number of students who were held back due to failing grades; at the time, 42% of the school district's budget was spent "re-educating" Bridgeport's failing students to enable them to pass on to the next grade.

The dental hygiene program also demonstrated that children were better able to resist communicable diseases, Dr. Fones noted. During the five-year period, there was a significant reduction in the number of cases of such diseases in the public schools. According to Dr. Fones, incidences of diphtheria were reduced by 50% (720 cases compared with 360 cases), measles by 66% (400 cases compared with 133 cases), and scarlet fever by 97% (282 cases compared with 10 cases).

The nation's press lauded the Bridgeport experiment, reporting "what one city has gained by taking care of children's teeth" had "increase[d] the average intelligence of the future generation." Another newspaper article enunciated that "decayed teeth are causing more harm in the human race than alcohol." Dr. Fones himself was fond of quoting a Popular Science magazine article, which declared that 95 million Americans "have decayed teeth" and that "dentistry's next step is to wipe out or prevent tooth decay by a systematic campaign of education on the care of teeth among children."

Put in perspective, the total population of the U.S. in 1919 was 106 million. With the opening of his hygienist school and the success of the Bridgeport school district education program, Dr. Fones had become a national figure.

Even so, Dr. Fones shut down his school in 1916, some three years after it had opened. During its operation he had trained 96 dental hygienists. There is no real explanation as to why it was shut down, but a number of factors likely contributed to his decision. Other schools following his design opened across the U.S. In addition, there were extensive demands on Dr. Fone's time to speak, write, and continue his professorship at Columbia University. He likely felt he could do more good lecturing and writing about decay prevention, and undoubtedly the financial rewards would have been greater than remaining a town dentist.

War on sugar

After World War I, Dr. Fones continued to gain national headlines in his quest against tooth decay. He railed before audiences and in numerous articles that "there should be no free sugar in the diet of a child from birth to fifteen years of age." In a 1920s newspaper article, C. Houston Goudiss, a prolific book and journal author on healthy foods, cited Dr. Fones' claim that "children should rely on natural sugars in fruit and milk and on the sugar made by their bodies from the intake of starchy food, such as bread, potatoes, and cereals."

Page 2

Continued from Page 1

threatened by the emerging profession and fought attempts to certify any kind of dental assistant (for example, in 1910 the Ohio College of Dental Surgery's course for "Dental Nurse and Assistant" was closed down by a "coalition of dentists"). The very concept was confusing; Edna Stowe Thomas, who would become Wyoming's first dental hygienist, recalled a 1921 conversation with a Wyoming state senator she was lobbying to enact the first dental hygienist statute in that state: "He asked me quite seriously, 'Now just what kind of an animal is a dental hygienist ?' "

In 1913, Dr. Fones founded a school for dental hygienists in Bridgeport, the first of its kind anywhere. Faculty at the school included the deans of the Harvard and Pennsylvania dental schools, seven professors from Yale, and two from Columbia. Perceived at the time as a women's-only profession, 27 students graduated that first year.

That same year, Dr. Fones also launched a program to provide trained dental hygienists to the Bridgeport public schools. The Bridgeport city government appropriated $5,000 to try the experiment for five years. One era newspaper described the experiment as involving "cleaning the children's teeth, tooth brush drills, lectures on the mouth care to older children, and education in the homes by means of pamphlets." Dr. Fones himself discovered that less than 10% of Bridgeport's schoolchildren were brushing their teeth daily.

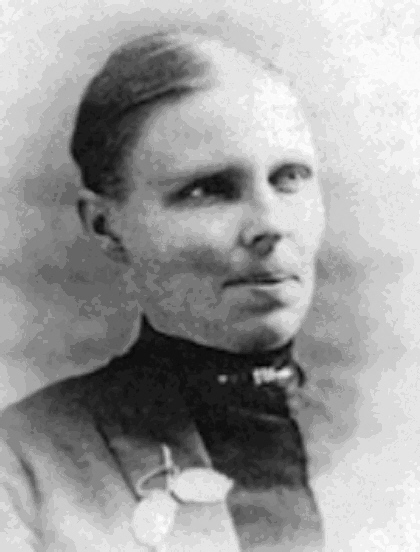

Irene Newman

But by 1919 the program had become fixed in the schools, and 26 hygienists were employed by the school district to service 20,000 school children. The same year Dr. Fones issued a report covering the five-year history of the program that contained some rather amazing statistics. He claimed his program had cut by 50% the number of students who were held back due to failing grades; at the time, 42% of the school district's budget was spent "re-educating" Bridgeport's failing students to enable them to pass on to the next grade.

Continued Page 3

CONTACT ME ddemers901@sonic.net